Rise of the Planet of the Apes is not to be associated with Tim Burton’s 2001 remake of Planet of the Apes. This is a completely different venture, looking to act a starting point from which any number of sequels could surely follow. On paper, director Rupert Wyatt appears to have been handed a difficult task- reimagining a franchise that first powered its way into Hollywood forty years ago and capturing the minds of a new generation. In reality, he’s taken that difficult task and created what will be remembered as one of the hits of the summer.

James Franco plays Will Rodman, a scientist working on a cure for neurological diseases. The inspiration behind his work is his father Charles (John Lithgow), suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Using chimpanzees as test subjects, his five years work has now culminated in a virus that repairs brain cells, and in fact improves the intelligence of the recipient. However, following an aggressive attack by one of the subjects at a crucial moment in a company presentation, he is ordered to cease his work and to kill the remaining chimpanzees. Upon discovering the new born of said aggressive chimp, he names it Caesar and decides to adopt it as his own, thus continuing his work from home. What follows is the story of the development and rise to prominence of Caesar (Anthony Serkis) himself.

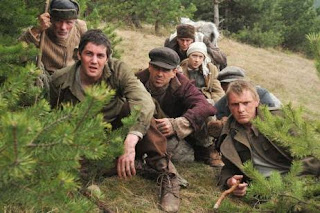

Rise is divided into three parts, and in offers a very distinct beginning, middle and end. The beginning focuses on Caesar’s integration with the human world, at first revelling in the marvels of his existence but then realising that there is so much more out there. The middle section of the film sees Caesar struggle with his identity during an encapsulation period, and finds integration with the other chimpanzees a daunting prospect. That said, his intelligence proves to be an insurmountable advantage. This leads us to the third and final part of the film, documenting Caesar’s rise as he attempts to leads his fellow primates to their freedom.

From the opening scene it is obvious that there will be a strong focus on the development of the primates, as we are shown hunters gathering up chimpanzees from their natural environment, and shipping them off to be experimented on. It is no secret as to where this franchise is eventually heading, be it in the inevitable sequel or further down the line, so the challenge for Wyatt is really in the telling of the evolutionary journey.

And for something that had the potential to be messy, it is expertly handled through a series of delicate moments during Caesar’s formative years. In fact, Rise becomes as much about Caesar’s coming of age as anything else, with his inability to speak allowing for some deep moments with Rodman - one in particular where he questions his own personal origins. The evolution is visually complete following a very tender scene in which Charles Rodman’s affliction is deteriorating and he is attempting to eat a fried egg with the back of his fork. Caesar slowly reaches out and turns the fork around, to the stunned silence of the father and son pairing that are present.

It is that kind of subtle crafting that really propels Rise above your standard summer blockbuster, and without the reliance on the apes this would not be possible. In all honestly, Caesar’s tale is remarkable, although not something we have not seen before. It is a standard fitting-in story, a person alone and attempting to find his place. His supporting cast are equally as stereotypical. There’s the wise go-to-guy, a performing orangutan named Maurice. And the hot headed muscle in the form of Buck the Gorilla. Not to mention Caesar’s initial rival, the playground bully Alpha. All that is really missing is a cringe worthy love story, but thankfully that was not to be.

Although the names of France, Pinto and Lithgow will be emblazoned across the various posters and dvd cases that see release, the apes provide the real cast using motion capture technology, courtesy of the Peter Jackson founded Weta visual effects studio. Although stereotypical, the characters offer a different feel to proceedings, and it is certainly interesting to see the chimps rise and overcome all the odds stacked against them. And Caesar certainly steals the show, with an amazingly humanistic feel to his performance.

Of the human characters, only Lithgow really stands out. His portrayal of Rodman senior is compelling and well rounded, and the vulnerability that he displays allows a memorable performance as a very likeable character. Franco’s performance is good but with little to showcase his own abilities as he did in 127 Hours, his bond with Caesar is strong but borne out of necessity rather than friendship, and that seriously impinges on what could have been a very strong relationship. His love interest Caroline Aranha (Freida Pinto), provides little other than a whole lot of standing around, and the role is a far cry from Slumdog Millionaire.

The supporting cast is a predictable mixture of good and bad, with a flat performance from Brian Cox (John Landon- the owner of the holding facility for chimps) eclipsed only be a very poor David Oyelowo. As a supposedly powerful man in charge of Will and his experiments he lacks any form of charisma whatsoever, rendering his character worthless. On a more positive note Tom Felton does well as an angry, snarling and unlikeable Dodge Landon, while David Hewlett does a great impression of a neighbour from hell, playing Hunsiker, who is a constant danger to the harmony of the Rodman household.

As far as science fiction goes “Planet of the Apes” (La Planète des singes) is up there with the best of them, and in an age governed by technology Pierre Boulle’s novel is just as thought provoking nowadays as it would have been back in 1963 when it was released. In fact, given modern biological and scientific advances it is perhaps more thought provoking now than ever before. It seems then that there is no better time than the present for a Hollywood reboot. The fact is, although farfetched, it is still a plausible scenario in the current age. Luckily, Rise doesn’t go down the route of providing an in-your-face warning, and the destructive force of technology remains nothing more than an undercurrent.

As much as this acts as an origin story, it is also a very watchable standalone film. It is certainly far better than many will have expected, and not laden with pointless action scenes which would have weighed it down. That said, the siege sequence towards the finale is intelligent and brilliantly crafted, and far more enjoyable than most seen in a summer blockbuster. The apes are a welcome reprieve from the expected norms, and the story is both well paced and well poised. Pity about the humans, though.

Rating:

4 / 5